A View into Life with a Hair Pulling Disorder

By Syeda Aiman Zehra

TW: Trichotillomania, Dermatillomania

I haven’t been to the parlor for a haircut since 2018. In 2017, I stopped braiding my hair—and I love braids. My mother gave up trying to convince me to let her oil my hair about a year and a half ago. When I entered LUMS, I ended my relationship with performance arts that spanned years of acting or dancing lead roles. Now, with every passing day, I have started saying more no’s than yes’s to opportunities to leave my house and I have come to equally dread the one thing I desire most: coming back to campus.

All of these choices have been solely dictated by an avoidance of overt exposure or movement of my hair. This obsessive behavior started around grade 8 or 9, but I was only able to name it when I Googled it two years ago. The word that stared back at me rewired my brain for the foreseeable future. Each letter in this word kept multiplying until it felt like the longest, heaviest word in my life: Trichotillomania.

Medically, trichotillomania (trich) is defined as one of the obsessive compulsive and related disorders, and entails strong impulses created by a set of triggers which results in the pulling of hair from any part of the body.

However, with any health related condition, the definition extends over to a much larger territory of the human experience. Which is to say, it doesn’t just end at the hair pulling.

***

Noor,* a student at LUMS struggling with trich since age 13, recounts: “I used to take a hijab to hide my trichotillomania situation…At LUMS, after a shower, I immediately blow dried my hair because I didn’t want my roommate to know…It was such a constant fear that every decision of my life began revolving around hiding those bald spots.”

This encroachment of agency does not stop at lifestyle choices. Oftentimes, for those with trich, an unforgiving cycle plays out where one trigger causes a hair pulling episode that creates a drastic imbalance in moods and self-esteem. This, in turn, may activate another psychological condition, which then acts as a trigger for trich. And so on. For Noor, this has played out so: “Around the same time [when trich started], depression, anxiety, OCD, and other issues were happening. I do not know a Noor without all of this.”

In a similar vein, Fatima Qazi, another student who reached out to The Post, relates that her journey started with dermatillomania—a disorder belonging to the same family that results in the picking of skin—but took up other things along the way. “I only picked on acne at first, but then it began mixing with everything. I started plucking new hairs, too, to achieve the same [pain induced] sensation. That’s where trich came in,” she says.

This infringement of both our psychological and physical experiences puts many of us at an impossible crossroads. The best prevention method for an episode is to throw ourselves into the public where we are likely not to pluck because embarrassment becomes a bigger motivator. But that puts our mental health at higher stakes. When surrounded by others, we become increasingly self conscious about the visibility of our bald spots. More than that, the public life may allow a third person to pass unwelcome judgement that can very easily trigger the next bad trich episode. “There’s this shock when they first see me, followed by asking me to expose myself even more to answer their questions. It’s that one look though that attacks your self-esteem and makes you feel especially disgusting and ugly,” says Qazi.

That’s how it goes almost every day.

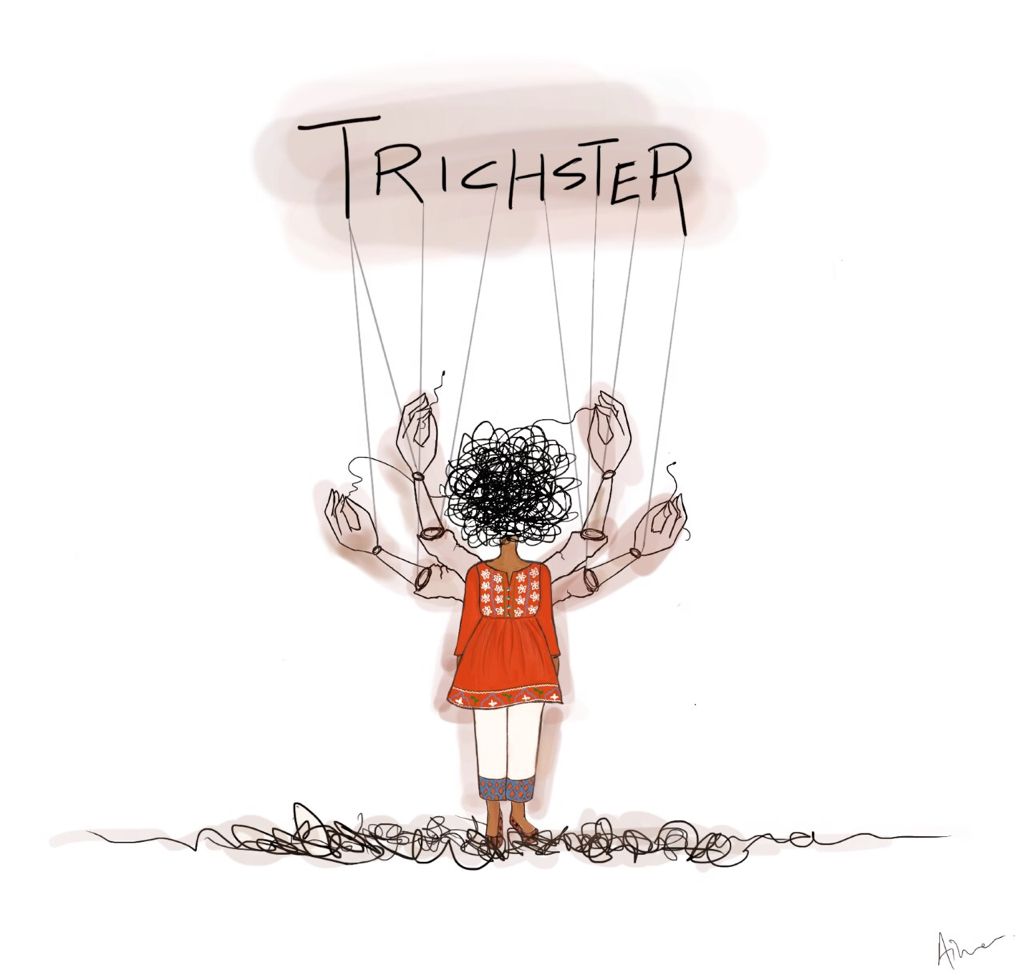

On the other hand, solitude becomes a perpetrator because of the presence of another force. It’s the same force that takes over you on the prayer mat when you’re mouthing words to a prayer, but your mind withdraws away to mundane thoughts and forgets which rakat you were on.

For us, solitude—especially the few moments before falling asleep—creates the risk of boredom to seep in, lull us into a distracted, restless state of mind, and push our consciousness to back stage. The force takes over. It puppeteers our hands to our head for a few minutes… an hour…and the next time we’re in full control of ourselves, a good few hours have passed. Our spine is ready to crack. The floor is covered with a sheet of freshly plucked hair. We scoop it up into a big hairball, heads bent, and throw away the day’s deed in the dustbin before anyone else can see.

“It’s like a blackout, you can’t stop until a certain amount of damage has been done,” Qazi explains.

***

Over the years, the three of us have been filling our tool box of informed and uninformed coping mechanisms.

I have kept planners, checklists, and reward systems. I have put close friends on video calls at night. I have gotten therapy and used stress balls. I have micromanaged to stay distracted. I have tired myself out extensively during the day so at night I’d fall asleep without leaving a window for an episode to sneak in.

Noor says: “I have put tape on my hands. I have added laal mirch to my fingers. I have worn caps to hide my hair. I have stuck Post Its on the walls to give me reminders. I have rubbed pen tips across my scalp to satisfy urges. I have gotten antidepressants.”

Qazi says: “I have Googled everything about cognitive behavioral therapy. I have read all the self-help books. I have meditated. I have used slime. I have switched to wearing full sleeves to hide my scars [from dermatillomania]. I have gotten antidepressants.”

Our toolbox is expansive because nothing lasts for long. Our list of triggers is wide and keeps changing with the reactions we receive. Perhaps it has something to do with the people closest to us wanting to find permanent solutions to something that is evolutional. And so, driving a mechanism towards permanence drives it out of use instead and we are pushed back to the start of the cycle.

Along the way, the biggest relief and the biggest surprise to all three of us has been that Google search moment where we realized we weren’t alone. It’s through these shared, lived experiences that come forth in our conversations with each other or the few others we have found or opened up to that we are able to breathe as ourselves, unabashedly.

***

In these conversations, there’s been mutual agreement and acceptance that recovery—both physically and mentally—might be a forever process when certain tropes keep floating in and out of the journey or haunt consistently.

This process becomes hard when, as a South Asian woman, your trich becomes part of the larger narrative of beauty standards and rishta cultures prevalent here. It is still okay for a man to start balding at an earlier age, but when a woman goes through the same thing, a recurring alienation takes form where all eyes are ready to gawk and tongues ready to taunt, shame, and guilt trip you. It becomes even harder when these are people closest to you, even if they mean well. It’s no wonder then that finding local support groups or individuals ready to speak about this is difficult. While up to every 4 in a 100*** people suffer from trich, there has been a curtain of silence attached because there is little empathy found on the other side.

It becomes hard when people compare something so deep seated in a history of factors to something grossly reductive like a nail biting habit to make sense of something they couldn’t otherwise. Because this way, there is room for them to philosophize your experience and provide baseless solutions: “It’s just a habit, God has given us all the beautiful gift of willpower, use it! You can’t possibly be this weak!”

It’s hard when you try to write an awareness piece on trich because you made a promise to yourself and others that you will tell this story—that it’s about time someone did. But, every time you sit down to type, an episode takes over you until it’s dawn and your headspace is full of hair and self-loathing, and the words in front of you don’t mean anything anymore.

Perhaps, then you go to the mirror to see the day’s worth of damage and instead of another breakdown and another bad day, maybe this day you shrug and say, in Noor’s words, “It is what it is. I won’t let it define me, but it is a part of me.” For that day, you try to take ownership of the environment that creates those triggers in the hopes of putting up a fair fight. And you hope too that the people occupying that space will be kinder today.

*This name has been changed for the sake of anonymity.

**These are US based statistics because unfortunately that kind of research is yet to be done here.