By Zoha Fareed Chishti ’23

The GPS tells me I have arrived at the destination– a house, in a closed-off street in Gulberg, where Dr. Mohammad Moiz (aka Unrellently Yours, Phuddina Chutney, and Shumaila Bhatti) was getting ready for their drag-comedy show happening later that evening. I call Moiz to confirm whether I am at the right destination. “Brown gate, colorful tyres on the wall?” they ask me. It is the right house. I, along with a friend, am escorted into the house, and up the stairs, to a room.

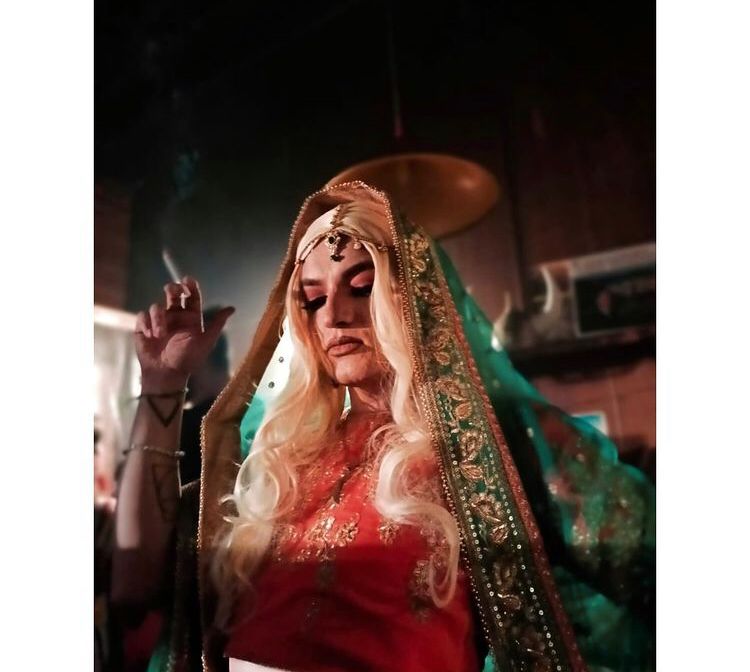

Moiz, already in a bright orange lehenga-choli, is getting their make-up done as we enter the room. They apologise for the state they are greeting us in: the room is scattered with makeup products, and there is a certain sense of hustle all around. Even within the hustle though, there is no sense of urgency. My friend and I take a seat, as Moiz continues to have foundation coated on their face.

My friend, an avid fan of Moiz’s work, asks them how they came up with the idea of Phuddina Chutney– and what prompted them to pioneer drag comedy in Pakistan. “Actually, I do not believe I pioneered it…” Moiz tells us. Instead, they believe that dirty comedy, and drag comedy alike, have always been present in Pakistan, especially in the rural landscapes. I follow this up with an example of the women in Punjabi villages– the tappay, gidday, even the folk songs are filled with profanities and innuendos that could easily be given an R rating, but, are very funny, and very much part of the culture. Moiz says this is also true for Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where they hail from. “There is of course an appetite for drag comedy in Pakistan– it’s part of our culture, people want it, my shows get sold out. That says something,” they finish.

I ask Moiz about the audience their drag show receives. “Everyone! Students, old people, young people, men, women, queer people… everyone comes to see me,” they answer. I follow this up with questioning whether the audiences differ from city to city. “Yes, I get more older aunties in Karachi. Older Lahori women are rare. Clifton/Defence crowds in Karachi are too bougie. Lahori girls always laugh with a hand to their faces,” they tell me. Their audience wants to have fun, but sometimes it takes its time opening up.

Steering the conversation away from their comedy, I ask Moiz why they argue against the secular model of feminism that is popular amongst students, and also certain movements like Aurat March adopt. “Religion plays a role in everyday lives, not just in South Asia, but the entire world. It’s unsustainable to remove your politics [from something that shapes your everyday life],” they explain. They also argue that the Global Right informs the Pakistani Right too– Orya Maqbool Jan taking inspiration from Trump’s bathroom ban is only one example, but that gets lost in translation, and the Left then blames Islam. They further explain that this is perhaps not the fault of the young people, because there is no room for critique. “The first time you actually get to explore; yourself, religion, everything, is when you are at university. So, it is natural to feel that distance from religion and build an identity [that is separated] from Islam,” they tell me. The fear of blasphemy, they argue, is so real, because of how defined the correct version of Islam has become in Pakistan. “There is no space for Khuda ki talaash [or what we call spirituality], then, in this codified version of Islam,” Moiz argues, “kisi k liye Islam ka expression hai paanch waqt ki namaz, kisi ke liye muharamm ka maatam, kisi ke liye sehwan sharif jaana, there is no single definition…”

I then ask them about the sudden increase in their Instagram audience after the Beela incident– especially because in one of the earlier episodes of their podcast, Stoned Alive, Moiz had maintained that they like having a smaller, niche, audience. I ask them how they navigate through this. “Jab main chota tha, I wanted to be a celebrity, now that I am, I don’t want to be,” they laugh. They tell me that they did not mind the increase in audience as such– the sudden influx was only after they had first posted about taking action against Beelas, but it has steadied since then. “Only the interested people are staying, and I like that,” they finish with a smile, “besides, I don’t get stuck on numbers, that’s how I navigate all this.”

Commenting on their popularity, my friend tells Moiz that she used their example in her class on gender and media. “Lo, ab mujhe LUMS ki classon main bhi parhatay hain,” Moiz winks at their friend sitting on the floor opposite to us. I also ask them what they think of performative activism, and woke culture. “Of course, support is substantial, even if it is performative,” they reply, “But main kitna depend kersakta hoon baaqi sab per?” They tell me that virtual, or otherwise, support helps, but only so much. At the end of the day, you have to fight your own battles. “Thaanay aor court tau khudi jaana hai, no one else can go for me,” they say slowly, trying their best not to smudge the pink stain that has just been added to their lips.

Once Moiz is ready, my friend and I drive them to the location for their show. We are chatting about the weather, Lahore, the traffic, when, as an afterthought, I ask them why they chose an MBBS degree. With a laugh, they very simply retort, “Well, what else are you going to do?” For the rest of the drive, I can hear a hum coming from the backseat. I identify it as the tune to Kajra Re, the hindi song. When we get to the destination, we bid Moiz goodbye as they get out of the car into the empty, dark, and slightly barricaded street. As we back the car, I hear Moiz tell the guard to let them in. “Mera he show hai!” echoes in the street we leave them in.